No one can ever really get inside an artistic partnership. Who knows why some people fit together, share a vision, finish each other’s sentences? Who knows why come artists come together to make work that is greater than anything they can accomplish alone? One of the great strengths of Made in England—and there are many—is that the documentary never tries to get inside Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s relationship. It doesn’t psychoanalyze them, or delve into their personal lives. What it does is shine a beautiful red-gelled spotlight on the films they created together.

Let’s get this out of the way: The movies made by the writing/directing/producing team Powell and Pressburger make me glad I was born. They make me want to be a better artist. Hell, they make me want to be a better person. It’s safe to say that I went into this documentary with high hopes—and it met them and exceeded them.

Made in England was directed by BAFTA and Emmy-winner David Hinton, it’s 131 minutes long, and it’s absolutely entrancing. The documentary is hosted by Martin Scorsese—and I say hosted and not narrated because it really feels like you’re sitting at a bar with Mr. Scorsese, and he’s excitedly telling you about his friends, Powell and Pressburger. (To be fair, he did become friends with Michael Powell, and even introduced him to his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmacher, and the two ended up getting married.) In a way, Made in England is of a piece with two documentaries Scorsese made himself: “A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese Through American Movies” and “My Voyage to Italy”, which serve almost as autobiopics. But while those two movies tell sweeping stories about US film and Italian film respectively, this one is a gorgeously involving dive into the work of one creative team.

We’re taken through brief stops in the pair’s early days (Powell in England and France, Pressburger in Hungary and Germany) before digging into their work together. One of the strongest elements of the documentary is that rather than focusing solely on their most famous wartime collaborations, the filmmakers spend a lot of time looking at the pair’s projects from the 1960s and ‘70s. While those weren’t as successful as the earlier work, I was happy to get more insight into how they tried to keep going even as the film industry became less supportive of their visions.

Powell-Pressburger are a unique case, and not just because the two of them shared the work and the credit. They named their company The Archers, and their films opened with this image:

And ended with some variation on this image:

In the early years of their collaboration, they were charged with making propaganda films for Britain. But because they had a powerful protector in producer J. Arthur Rank, they were able to interpret “propaganda” in a surprising way. A film about WWI-era German spies (The Spy in Black) takes the time to commiserate with the men about their meager rations, while another, about German soldiers hiding among a Canadian Hutterite community (The 49th Parallel) treats them as humans beings who are capable of change, and even gives one of them a redemption arc. When they were asked to make a film about British-American cooperation as WWII came to an end, they did it by creating A Matter of Life and Death, in which an American woman falls in love with a British man who’s supposed to be dead, and cosmic hijinks ensue. When they wanted to look directly at military life it was through an update on The Canterbury Tales, where a British and American soldier become friends with a Land Girl in Kent during a leave, or with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, a warm, sad, gently comic story of forty years in the life of Major-General Clive Wynne-Candy, an aging career soldier who spends most of the movie meditating on his friendships and romances rather than exploits in battle. After the war, however, changes in the British studio system, and in public taste, meant that they were largely forgotten by the 1970s, and it wasn’t until younger American filmmakers including Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and George Romero championed their work that their films were recognized as classics.

Now, between work by film historian Ian Christie, The Film Foundation, the British Film Institute, the Criterion Collection, and others, most of their films have been restored (many of their movies had been re-edited—or perhaps it’s more fair to say butchered—for TV) and re-released.

Made in England creates a beautiful balance between the joy of Powell and Pressburger’s heady early days, being brutally realistic about the struggles in their later years, and showing them collecting various lifetime achievement awards once a younger generation had yelled about them enough. The doc is able to end on a somewhat positive note… until you think about all the films we didn’t get because the movie industry wouldn’t rally around a pair of born filmmakers.

Michael Powell started out as a British banker, but luckily for us all escaped to Nice, France, to work as a studio hand for silent film director Rex Ingram. He worked his way up, doing photography, helping with scripts, and performing slapstick comedy in shorts, before becoming a director. In 1939, the producer Alexander Korda brought him on to direct a film based on J. S. Clouston’s novel The Spy in Black, and introduced him to his newly hired script doctor, Emeric Pressburger. Pressburger had been a journalist in Hungary before breaking in as a screenwriter in Weimar Berlin’s iconic film industry. In 1933 he was fired along with all the other Jewish members of the industry, and, luckily for us all, made it to Paris before moving on to England, where he was a stateless refugee from 1935 [“Emeric was classified as an enemy alien because he had fled from Germany… Throughout the war, while he and Michael Powell were making masterpiece after masterpiece—films that were supporting the war effort—[Emeric] was forced to report to the police once a week, obey a curfew, and unable sometimes to go on location where the unit was filming.”] until finally gaining British citizenship in 1946. He was the one who brought a sense of European sophistication, empathy for the enemy, and a sense of terror and danger of their global situation, while Powell brought startling visuals and a mystical sense of nature that pushed some of their films into full surrealism.

Powell and Pressburger’s film partnership continued on and off for over 30 years, and produced 24 films, including The Spy in Black, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing, 49th Parallel, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Canterbury Tale, I Know Where I’m Going!, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, Gone to Earth, The Tales of Hoffmann, The Battle of the River Plate, and Ill Met by Moonlight.

Of their entire oeuvre, I’d say seven are all-time, must-watch, what-do-you-MEAN-you-haven’t-seen-it-yet??? cinematic masterpieces, three are classics of their subgenres, one is the greatest film ever made about the artistic process, and one that be my pick if I was on a crashing plane and I only had time for one more movie.

One of the joys of the documentary is a parallel with another film doc: In Hitchcock/Truffaut we learn that Hitchcock was in a bit of a slump when a young Francoise Truffaut wrote him the fan letter that led to the iconic book-length interview, itself later tuned into a documentary that I cannot recommend highly enough (it’s currently on Tubi!).

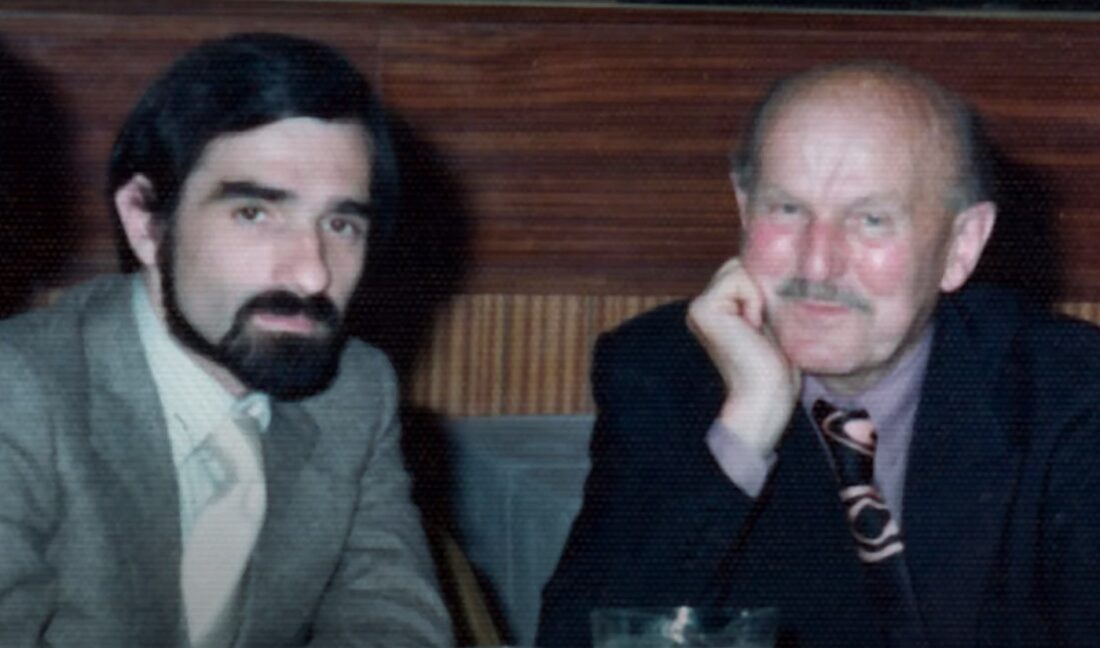

Made in England tells a similar story—Michael Powell was near broke, forgotten by a British film industry that considered his work with Pressburger passe. Then Martin Scorsese turned up in London shortly after Taxi Driver, and asked around until a producer who knew Powell was able to arrange a meeting. Powell had no idea a new wave of Americans had fallen in love with his work. Scorsese tells this story, saying again and again that he can’t believe his hero had become his friend.

And I know, there’s been some grumbling on some corners of the internet that Scorsese has become a somewhat cuddly meme-ified version of himself. But I would argue that as much as the documentary runs with the “Martin Scorsese, Film Grandpa” element, it does so in order to guide us into the true wonder of the movie, which is: most of Made In England’s runtime is Scorsese talking us through scenes from Powell-Pressburger’s films, analyzing their use of color, how they worked with edits, matte paintings, how they turned Shepperton Studios into the Himalayas, how they turned their actors faces into paintings, He talks about the use of color in Black Narcissus, the way the duo wove music and visuals together for Tales of Hoffman, and he goes into a deep analysis of the spiritual themes of A Canterbury Tale. And as if that wasn’t enough, he relates a lot of his analyses back to choices he made in his own films. This documentary is a slightly-more-than-two-hour-long masterclass on moviemaking.

I should also make it clear that Made in England isn’t hagiography by any means, and Scorsese also spends time pointing out films that didn’t quite work. Later films like The Battle of the River Plate and Ill Met By Moonlight still had great moments, but they didn’t have the spark of earlier projects. But even the declining years are balanced with a long discussion of Peeping Tom, a Michael Powell solo project that somehow manages to be the more fucked-up version of Psycho, and, from a certain point of view, a precursor to both The Fabelmans and Strange Days. It’s an extraordinary film. (I’m not just being an edgelord dickhead when I say it’s what Psycho could have been—I like Psycho, very much, and I find Hitchcock fascinating, but Peeping Tom is like Psycho with the fucking training wheels off.) It was also the movie that effectively ended Michael Powell’s career—British critics absolutely ripped it to shreds, and It was seen as so shocking and disturbing that I don’t think any viewing public gave it a fair shot for a while.

A hilarious element of the film is that Scorsese presents himself as a sort of street-level movie lover, overwhelmed by the work of Powell-Pressburger. “These days I’m told that Powell-Pressburger represents something called ‘English Romanticism’, but I don’t really know what that is. To me the overwhelming impression of their films has always had to do with color, light, movement, and a sense of music.” Disingenuous? A little “aw shucks” coming from our Greatest Living Filmmaker? Sure—but this movie isn’t really about applying any theory to Powell-Pressburger’s work. Scorsese, as much as he analyses their films and his own, comes back again and again to how they make him feel. The documentary puts its focus on the emotional reaction, not an intellectual one, which I think is perfect for this. As much as I love picking things apart, when it comes to Powell-Pressburger I really just want to go door-to-door, gently grabbing people by their lapels and demanding they watch the movies.

An 80-year-old master filmmaker gives hours of his time over to talking about these movies, in incredible depth, with boundless enthusiasm. What an act of love and generosity this is, for Scorsese to take the time to show us these films through his eyes.

To be somewhat personal for a moment: I have, for a while now, been just barely bobbing on the surface of what appears to be bottomless despair. (Not just because of the state of the world—not that it’s helping.) What I think about, when the undertow gets too strong, is that at least I’ve been able to dedicate an enormous portion of my life to the study of art. How lucky am I, to be alive at the same time as Martin Scorsese? To get to see his films, to get to hear him talk about work that he loves? Twice now, I’ve been able to attend screenings that Mr. Scorsese introduced, one for The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (I sat next to Fran Leibowitz!) and one, just a few weeks ago, for Black Narcissus. Once I got to see Thelma Schoonmacher introduce The Red Shoes. (She spoiled the ending! The crowd of tiny child ballerinas gasped in horror! Iconic!) Over this past month I’ve rearranged my schedule to run up to the Museum of Modern Art to see a good bit of the “Cinema Unbound: The Creative World of Powell-and Pressburger” retrospective that hosted Made in England after its U.S. premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival. I live in a city that allows me to do this. How lucky am I to live in a place that is stable enough, for now, to lose myself in film and words and art. What else can I possibly do but keep trying to talk about it, to insist that it matters as much as life and death?

The fourth item of The Archers’ Manifesto (of course they had a manifesto) was this: “No artist believes in escapism. And we secretly believe that no audience does. We have proved, at any rate, that they will pay to see the truth, for other reasons than her nakedness.” Made In England showcases this truth beautifully, and serves as a reminder that a life in art is always worth it, even when it doesn’t feel like it.

Made in England is out in limited release now—watch out for showtimes, it’s more than worth it!